In the summer of 1995, my friend Robert Morris and I decided to start a startup. The PR campaign leading up to Netscape's IPO was running full blast then, and there was a lot of talk in the press about online commerce. At the time there might have been thirty actual stores on the Web, all made by hand. If there were going to be a lot of online stores, there would need to be software for making them, so we decided to write some.

For the first week or so we intended to make this an ordinary desktop application. Then one day we had the idea of making the software run on our web server, using the browser as an interface. We tried rewriting the software to work over the Web, and it was clear that this was the way to go. If we wrote our software to run on the server, it would be a lot easier for the users and for us as well.

This turned out to be a good plan. Now, as Yahoo Store, this software is the most popular online store builder, with over 20,000 users.

When we started Viaweb, hardly anyone understood what we meant when we said that the software ran on the server. It was not until Hotmail was launched a year later that people started to get it. Now everyone knows that this is a valid approach. There is a name now for what we were: an Application Service Provider, or ASP.

I think a lot of the next generation of software will be written on this model. Even Microsoft, who have the most to lose, seem to see the inevitability of moving some things off the desktop. If software moves off the desktop and onto servers, it will mean a very different world for developers. This essay describes the surprising things we saw, as some of the first visitors to this new world. To the extent software does move onto servers, what I'm describing here is the future.

When we look back on the desktop software era, I think we'll marvel at the inconveniences people put up with, just as we marvel now at what early car owners put up with. For the first twenty or thirty years, you had to be a car expert to own a car. But cars were such a big win that lots of people who weren't car experts wanted to have them as well.

Computers are in this phase now. When you own a desktop computer, you end up learning a lot more than you wanted to know about what's happening inside it. But more than half the households in the US own one. My mother has a computer that she uses for email and for keeping accounts. A couple years ago she was alarmed to receive a letter from Apple, offering her a discount on a new version of the operating system. There's something wrong when a sixty-five-year-old woman who wants to use a computer for email and accounts has to think about installing new operating systems. Ordinary users shouldn't even know the words "operating system," much less "device driver" or "patch."

There is now another way to deliver software that will save users from becoming system administrators. Web-based applications are programs that run on web servers and use web pages as the user interface. For the average user this new kind of software will be easier, cheaper, more mobile, more reliable, and often more powerful than desktop software.

With web-based software, most users won't have to think about anything except the applications they use. All the messy, changing stuff will be sitting on a server somewhere, maintained by the kind of people who are good at that kind of thing. And so you won't ordinarily need a computer, per se, to use software. All you'll need will be something with a keyboard, a screen, and a web browser. Maybe it will have wireless Internet access. Maybe it will also be your cell phone. Whatever it is, it will be consumer electronics: something that costs about $200, and that people choose mostly based on how the case looks. You'll pay more for Internet services than you do for the hardware, just as you do now with telephones.1

It will take about a tenth of a second for a click to get to the server and back, so users of heavily interactive software, like Photoshop, will still want to have the computations happening on the desktop. But if you look at the kind of things most people use computers for, a tenth of a second latency would not be a problem. My mother doesn't really need a desktop computer, and there are a lot of people like her.

Near my house there is a car with a bumper sticker that reads "death before inconvenience." Most people, most of the time, will take whatever choice requires least work. If web-based software wins, it will be because it's more convenient. And it looks as if it will be, for users and developers both.

To use a purely web-based application, all you need is a browser connected to the Internet. So you can use a web-based application anywhere. When you install software on your desktop computer, you can only use it on that computer. Worse still, your files are trapped on that computer. The inconvenience of this model becomes more and more evident as people get used to networks.

The thin end of the wedge here was web-based email. Millions of people now realize that you should have access to email messages no matter where you are. And if you can see your email, why not your calendar? If you can discuss a document with your colleagues, why can't you edit it? Why should any of your data be trapped on some computer sitting on a faraway desk?

The whole idea of "your computer" is going away, and being replaced with "your data." You should be able to get at your data from any computer. Or rather, any client, and a client doesn't have to be a computer.

Clients shouldn't store data; they should be like telephones. In fact they may become telephones, or vice versa. And as clients get smaller, you have another reason not to keep your data on them: something you carry around with you can be lost or stolen. Leaving your PDA in a taxi is like a disk crash, except your data is handed to someone else instead of being vaporized.

With purely web-based software, neither your data nor the applications are kept on the client. So you don't have to install anything to use it. And when there's no installation, you don't have to worry about installation going wrong. There can't be incompatibilities between the application and your operating system, because the software doesn't run on your operating system.

Because it needs no installation, it will be easy, and common, to try web-based software before you "buy" it. You should expect to be able to test-drive any web-based application for free, just by going to the site where it's offered. At Viaweb our whole site was like a big arrow pointing users to the test drive.

After trying the demo, signing up for the service should require nothing more than filling out a brief form. And that should be the last work the user has to do. With web-based software, you should get new releases without paying extra, or doing any work, or possibly even knowing about it.

Upgrades won't be the big shocks they are now. Over time applications will quietly grow more powerful. This will take some effort on the part of the developers. They will have to design software so it can be updated without confusing the users. That's a new problem, but there are ways to solve it.

With web-based applications, everyone uses the same version, and bugs can be fixed as soon as they're discovered. So web-based software should have far fewer bugs than desktop software. At Viaweb, I doubt we ever had ten known bugs at any one time. That's orders of magnitude better than desktop software.

Web-based applications can be used by several people at the same time. This is an obvious win for collaborative applications, but I bet users will start to want this in most applications once they realize it's possible. It will often be useful to let two people edit the same document, for example. Viaweb let multiple users edit a site simultaneously, more because that was the right way to write the software than because we expected users to want to, but it turned out many did.

When you use a web-based application, your data will be safer. Disk crashes won't be a thing of the past, but users won't hear about them anymore. They'll happen within server farms. And companies offering web-based applications will actually do backups— not only because they'll have real system administrators worrying about such things, but because an ASP that does lose people's data will be in big, big trouble. When people lose their own data in a disk crash, they can't get that mad, because they only have themselves to be mad at. When a company loses their data for them, they'll get a lot madder.

Finally, web-based software should be less vulnerable to viruses. If the client doesn't run anything except a browser, there's less chance of running viruses, and no data locally to damage. And a program that attacked the servers themselves should find them well defended.2

For users, web-based software will be less stressful. I think if you looked inside the average Windows user you'd find a huge and pretty much untapped desire for software meeting that description. Unleashed, it could be a powerful force.

To developers, the most conspicuous difference between web based and desktop software is that a web-based application is not a single piece of code. It will be a collection of programs of different types rather than a single big binary. And so designing web-based software is like designing a city rather than a building: as well as buildings you need roads, street signs, utilities, police and fire departments, and plans for both growth and various kinds of disasters.

At Viaweb, software included fairly big applications that users talked to directly, programs those programs used, programs that ran constantly in the background looking for problems, programs that tried to restart things if they broke, programs that ran occasionally to compile statistics or build indexes for searches, programs we ran explicitly to garbage-collect resources or to move or restore data, programs that pretended to be users (to measure performance or expose bugs), programs for diagnosing network troubles, programs for doing backups, interfaces to outside services, software that drove an impressive collection of dials displaying real-time server statistics (a hit with visitors, but indispensable for us too), modifications (including bug fixes) to open source software, and a great many configuration files and settings. Trevor Blackwell wrote a spectacular program for moving stores to new servers across the country, without shutting them down, after we were bought by Yahoo. Programs paged us, sent faxes and email to users, conducted transactions with credit card processors, and talked to one another through sockets, pipes, HTTP requests, SSH, UDP packets, shared memory, and files. Some of Viaweb even consisted of the absence of programs, since one of the keys to Unix security is not to run unnecessary utilities that people might use to break into your servers.

It did not end with software. We spent a lot of time thinking about server configurations. We built the servers ourselves, from components—partly to save money, and partly to get exactly what we wanted. We had to think about whether our upstream ISP had fast enough connections to all the backbones. We serially dated RAID suppliers.

But hardware is not just something to worry about. When you control it you can do more for users. With a desktop application, you can specify certain minimum hardware, but you can't add more. If you administer the servers, you can in one step enable all your users to page people, or send faxes, or send commands by phone, or process credit cards, etc, just by installing the relevant hardware. We always looked for new ways to add features with hardware, not just because it pleased users, but also as a way to distinguish ourselves from competitors who (either because they sold desktop software, or resold web-based applications through ISPs) didn't have direct control over the hardware.

Because the software in a web-based application will be a collection of programs rather than a single binary, it can be written in any number of different languages. When you're writing desktop software, you're practically forced to write the application in the same language as the underlying operating system—meaning C and C++. And so these languages (especially among non technical people like managers and VCs) got to be considered as the languages for "serious" software development. But that was just an artifact of the way desktop software had to be delivered. For server-based software you can use any language you want.3 Today a lot of the top hackers are using languages far removed from C and C++: Perl, Python, and even Lisp.

With server-based software, no one can tell you what language to use, because you control the whole system, right down to the hardware. Different languages are good for different tasks. You can use whichever is best for each. And when you have competitors, "you can" means "you must" (we'll return to this later), because if you don't take advantage of this possibility, your competitors will.

Most of our competitors used C and C++, and this made their software visibly inferior because (among other things), they had no way around the statelessness of CGI scripts. If you were going to change something, all the changes had to happen on one page, with an Update button at the bottom. As I explain in Chapter 12, by using Lisp, which many people still consider a research language, we could make the Viaweb editor behave more like desktop software.

One of the most important changes in this new world is the way you do releases. In the desktop software business, doing a release is a huge trauma, in which the whole company sweats and strains to push out a single, giant piece of code. Obvious comparisons suggest themselves, both to the process and the resulting product.

With server-based software, you can make changes almost as you would in a program you were writing for yourself. You release software as a series of incremental changes instead of an occasional big explosion. A typical desktop software company might do one or two releases a year. At Viaweb we often did three to five releases a day.

When you switch to this new model, you realize how much software development is affected by the way it is released. Many of the nastiest problems you see in the desktop software business are due to the catastrophic nature of releases.

When you release only one new version a year, you tend to deal with bugs wholesale. Some time before the release date you assemble a new version in which half the code has been torn out and replaced, introducing countless bugs. Then a squad of QA people step in and start counting them, and the programmers work down the list, fixing them. They do not generally get to the end of the list, and indeed, no one is sure where the end is. It's like fishing rubble out of a pond. You never really know what's happening inside the software. At best you end up with a statistical sort of correctness.

With server-based software, most of the change is small and incremental. That in itself is less likely to introduce bugs. It also means you know what to test most carefully when you're about to release software: the last thing you changed. You end up with a much firmer grip on the code. As a general rule, you do know what's happening inside it. You don't have the source code memorized, of course, but when you read the source you do it like a pilot scanning the instrument panel, not like a detective trying to solve a mystery.

Desktop software breeds a certain fatalism about bugs. You Know you're shipping something loaded with bugs, and you've even set up mechanisms to compensate for it (e.g. patch releases). So why worry about a few more? Soon you're releasing whole features you know are broken. Apple did this a few years ago. They felt under pressure to release their new OS, whose release date had already slipped four times, but some of the software (support for CDs and DVDs) wasn't ready. The solution? They released the OS without the unfinished parts, and users had to install them later.

With web-based software, you never have to release software before it works, and you can release it as soon as it does work.

The industry veteran may be thinking: it's a fine-sounding idea to say that you never have to release software before it works, but what happens when you've promised to deliver a new version of your software by a certain date? With web-based software, you wouldn't make such a promise, because there are no versions. Your software changes gradually and continuously. Some changes might be bigger than others, but the idea of versions just doesn't naturally fit onto web-based software.

If anyone remembers Viaweb this might sound odd, because we were always announcing new versions. This was done entirely for PR purposes. The trade press, we learned, thinks in version numbers. They will give you major coverage for a major release, meaning a new first digit on the version number, and generally a paragraph at most for a point release, meaning a new digit after the decimal point.

Some of our competitors were offering desktop software and actually had version numbers. And for these releases, the mere fact of which seemed to us evidence of their backwardness, they would get all kinds of publicity. We didn't want to miss out, so we started giving version numbers to our software too. When we wanted some publicity, we'd make a list of all the features we'd added since the last "release," stick a new version number on the software, and issue a press release saying that the new version was available immediately. Amazingly, no one ever called us on it.

By the time we were bought, we had done this three times, so we were on Version 4. Version 4.1 if I remember correctly. Once Viaweb became Yahoo Store there was no longer such a desperate need for publicity, so although the software continued to evolve, the whole idea of version numbers was quietly dropped.

The other major technical advantage of web-based software is that you can reproduce most bugs. You have the users' data right there on your disk. If someone breaks your software, you don't have to try to guess what's going on, as you would with desktop software: you should be able to reproduce the error while they're on the phone with you. You might even know about it already, if you have code for noticing errors built into your application.

Web-based software gets used round the clock, so everything you do is immediately put through the wringer. Bugs turn up quickly.

Software companies are sometimes accused of letting the users debug their software. And that is just what I'm advocating. For web-based software it's actually a good plan, because the bugs are fewer and transient. When you release software gradually you get far fewer bugs to start with. And when you can reproduce errors and release changes instantly, you can find and fix most bugs as soon as they appear. We never had enough bugs at any one time to bother with a formal bug-tracking system.

You should test changes before you release them, of course, so no major bugs should get released. Those few that inevitably slip through will involve borderline cases and will only affect the few users who encounter them before someone calls in to complain. As long as you fix bugs right away, the net effect, for the average user, is far fewer bugs. I doubt the average Viaweb user ever saw a bug.

Fixing fresh bugs is easier than fixing old ones. It's usually fairly quick to find a bug in code you just wrote. When it turns up you often know what's wrong before you even look at the source, because you were already worrying about it subconsciously. Fixing a bug in something you wrote six months ago (the average case if you release once a year) is a lot more work. And since you don't understand the code as well, you're more likely to fix it in an ugly way, or even introduce more bugs.4

When you catch bugs early, you also get fewer compound bugs. Compound bugs are two separate bugs that interact: you trip going downstairs, and when you reach for the handrail it comes off in your hand. In software this kind of bug is the hardest to find, and also tends to have the worst consequences.5 The traditional "break everything and then filter out the bugs" approach inherently yields a lot of compound bugs. And software released in a series of small changes inherently tends not to. The floors are constantly being swept clean of any loose objects that might later get stuck in something.

It helps if you use a technique called functional programming. Functional programming means avoiding side effects. It's something you're more likely to see in research papers than commercial software, but for web-based applications it turns out to be really useful. It's hard to write entire programs as purely functional code, but you can write substantial chunks this way. It makes those parts of your software easier to test, because they have no state, and that is very convenient in a situation where you are constantly making and testing small modifications. I wrote much of Viaweb's editor in this style, and we made our scripting language, RTML, a purely functional language.

People from the desktop software business will find this hard to credit, but at Viaweb bugs became almost a game. Since most released bugs involved borderline cases, the users who encountered them were likely to be advanced users, pushing the envelope. Advanced users are more forgiving about bugs, especially since you probably introduced them in the course of adding some feature they were asking for. In fact, because bugs were rare and you had to be doing sophisticated things to see them, advanced users were often proud to catch one. They would call support in a spirit more of triumph than anger, as if they had scored points off us.

When you can reproduce errors, it changes your approach to customer support. At most software companies, support is offered as a way to make customers feel better. They're either calling you about a known bug, or they're just doing something wrong and you have to figure out what. In either case there's not much you can learn from them. And so you tend to view support calls as a pain in the ass that you want to isolate from your developers as much as possible.

This was not how things worked at Viaweb. At Viaweb, support was free, because we wanted to hear from customers. If someone had a problem, we wanted to know about it right away so we could reproduce the error and release a fix.

So at Viaweb the developers were always in close contact with support. The customer support people were about thirty feet away from the programmers, and knew they could always interrupt anything with a report of a genuine bug. We would leave a board meeting to fix a serious bug.

Our approach to support made everyone happier. The customers were delighted. Just imagine how it would feel to call a support line and be treated as someone bringing important news. The customer support people liked it because it meant they could help the users, instead of reading scripts at them. And the programmers liked it because they could reproduce bugs instead of just hearing vague second-hand reports about them.

Our policy of fixing bugs on the fly changed the relationship between customer support people and hackers. At most software companies, support people are underpaid human shields, and hackers are little copies of God the Father, creators of the world. Whatever the procedure for reporting bugs, it is likely to be one-directional: support people who hear about bugs fill out some form that eventually gets passed on (possibly via QA) to programmers, who put it on their list of things to do. It was different at Viaweb. Within a minute of hearing about a bug from a customer, the support people could be standing next to a programmer hearing him say "Shit, you're right, it's a bug." It delighted the support people to hear that "you're right" from the hackers. They used to bring us bugs with the same expectant air as a cat bringing you a mouse it has just killed. It also made them more careful in judging the seriousness of a bug, because now their honor was on the line.

After we were bought by Yahoo, the customer support people were moved far away from the programmers. It was only then that we realized they were effectively QA and to some extent marketing as well. In addition to catching bugs, they were the keepers of the knowledge of vaguer, bug like things, like features that confused users.6 They were also a kind of proxy focus group; we could ask them which of two new features users wanted more, and they were always right.

Being able to release software immediately is a big motivator. Often as I was walking to work I would think of some change I wanted to make to the software, and do it that day. This worked for bigger features as well. Even if something was going to take two weeks to write (few projects took longer), I knew I could see the effect in the software as soon as it was done.

If I'd had to wait a year for the next release, I would have shelved most of these ideas, for a while at least. The thing about ideas, though, is that they lead to more ideas. Have you ever noticed that when you sit down to write something, half the ideas that end up in it are ones you thought of while writing? The same thing happens with software. Working to implement one idea gives you more ideas. So shelving an idea costs you not only that delay in implementing it, but also all the ideas that implementing it would have led to. In fact, shelving an idea probably even inhibits new ideas: as you start to think of some new feature, you catch sight of the shelf and think, "but I already have a lot of new things I want to do for the next release."

What big companies do instead of implementing features is plan them. At Viaweb we sometimes ran into trouble on this account. Investors and analysts would ask us what we had planned for the future. The truthful answer would have been, we didn't have any plans. We had general ideas about things we wanted to improve, but if we knew how we would have done it already. What were we going to do in the next six months? Whatever looked like the biggest win. I don't know if I ever dared give this answer, but that was the truth. Plans are just another word for ideas on the shelf. When we thought of good ideas, we implemented them.

At Viaweb, as at many software companies, most code had one definite owner. But when you owned something you really owned it: no one except the owner of a piece of software had to approve (or even know about) a release. There was no protection against breakage except the fear of looking like an idiot to one's peers, and that was more than enough. I may have given the impression that we just blithely plowed forward writing code. We did go fast, but we thought very carefully before we released software onto those servers. And paying attention is more important to reliability than moving slowly. Because he pays close attention, a Navy pilot can land a 40,000 lb. aircraft at 140 miles per hour on a pitching carrier deck, at night, more safely than the average teenager can cut a bagel.

This way of writing software is a double-edged sword of course. It works a lot better for a small team of good, trusted programmers than it would for a big company of mediocre ones, where bad ideas are caught by committees instead of the people who had them.

Fortunately, web-based software does require fewer programmers. I once worked for a medium-sized desktop software company that had over 100 people working in engineering as a whole. Only 13 of these were in product development. All the rest were working on releases, ports, and so on. With web-based software, all you need (at most) are the 13 people, because there are no releases, ports, and so on.

Viaweb was written by just three people.7 I was always under pressure to hire more, because we wanted to get bought, and we knew that buyers would have a hard time paying a high price for a company with only three programmers. (Solution: we hired more, but created new projects for them.)

When you can write software with fewer programmers, it saves you more than money. As Fred Brooks pointed out in The Mythical Man-Month, adding people to a project tends to slow it down. The number of possible connections between developers grows exponentially with the size of the group.8 The larger the group, the more time they'll spend in meetings negotiating how their software will work together, and the more bugs they'll get from unforeseen interactions. Fortunately, this process also works in reverse: as groups get smaller, software development gets exponentially more efficient. I can't remember the programmers at Viaweb ever having an actual meeting. We never had more to say at any one time than we could say as we were walking to lunch.

If there is a downside here, it is that all the programmers have to be to some degree system administrators as well. When you're hosting software, someone has to be watching the servers, and in practice the only people who can do this properly are the ones who wrote the software. At Viaweb our system had so many components and changed so frequently that there was no definite border between software and infrastructure. Arbitrarily declaring such a border would have constrained our design choices. And so although we were constantly hoping that one day ("in a couple months") everything would be stable enough that we could hire someone whose job was just to worry about the servers, it never happened.

I don't think it could be any other way, as long as you're still actively developing the product. Web-based software is never going to be something you write, check in, and go home. It's a live thing, running on your servers right now. A bad bug might not just crash one user's process; it could crash them all. If a bug in your code corrupts some data on disk, you have to fix it. And so on. We found that you don't have to watch the servers every minute (after the first year or so), but you definitely want to keep an eye on things you've changed recently. You don't release code late at night and then go home.

With server-based software, you're in closer touch with your code. You can also be in closer touch with your users. Intuit is famous for introducing themselves to customers at retail stores and asking to follow them home. If you've ever watched someone use your software for the first time, you know what surprises must have awaited them.

Software should do what users think it will. But you can't have any idea what users will be thinking, believe me, until you watch them. And server-based software gives you unprecedented information about their behavior. You're not limited to small, artificial focus groups. You can see every click made by every user. You have to consider carefully what you're going to look at, because you don't want to violate users' privacy, but even the most general statistical sampling can be very useful.

When you have the users on your server, you don't have to rely on benchmarks, for example. Benchmarks are simulated users. With server-based software, you can watch actual users. To decide what to optimize, just log into a server and see what's consuming all the CPU. And you know when to stop optimizing too: we eventually got the Viaweb editor to the point where it was memory bound rather than CPU-bound, and since there was nothing we could do to decrease the size of users' data (well, nothing easy), we knew we might as well stop there.

Efficiency matters for server-based software, because you're paying for the hardware. The number of users you can support per server is the divisor of your capital cost, so if you can make your software very efficient, you can undersell competitors and still make a profit. At Viaweb we got the capital cost per user down to about $5. It would be less now, probably less than the cost of sending them the first month's bill. Hardware is free now, if your software is reasonably efficient.

Watching users can guide you in design as well as optimization. Viaweb had a scripting language called RTML that let advanced users define their own page styles. We found that RTML became a kind of suggestion box, because users only used it when the predefined page styles couldn't do what they wanted. Originally the editor put button bars across the page, for example, but after a number of users used RTML to put buttons down the left side, we made that the default in the predefined page styles.

Finally, by watching users you can often tell when they're in trouble. And since the customer is always right, that's a sign of something you need to fix. At Viaweb the key to getting users was the online test drive. It was not just a series of slides built by marketing people. In our test drive, users actually used the software. It took about five minutes, and at the end of it they had built a real, working store.

The test drive was the way we got nearly all our new users. I think it will be the same for most web-based applications. If users can get through a test drive successfully, they'll like the product. If they get confused or bored, they won't. So anything we could do to get more people through the test drive would increase our growth rate.

I studied click trails of people taking the test drive and found that at a certain step they would get confused and click on the browser's Back button. (If you try writing web-based applications, you'll find the Back button becomes one of your most interesting philosophical problems.) So I added a message at that point, telling users they were nearly finished, and reminding them not to click on the Back button. Another great thing about web-based software is that you get instant feedback from changes: the number of people completing the test drive rose immediately from 60% to 90%. And since the number of new users was a function of the number of completed test drives, our revenue growth increased by 50%, just from that change.

In the early 1990s I read an article that described software as a "subscription business." At first this seemed a very cynical statement. But later I realized that it reflects reality: software development is an ongoing process. I think it's cleaner if you openly charge subscription fees, instead of forcing people to keep buying and installing new versions so they'll keep paying you. And fortunately, subscriptions are the natural way to bill for web-based applications.

Hosting applications is an area where companies will play a role that is not likely to be filled by freeware. Hosting applications is a lot of stress, and has real expenses. No one will want to do it for free.

For companies, web-based applications are an ideal source of revenue. Instead of starting each quarter with a blank slate, you have a recurring revenue stream. Because your software evolves gradually, you don't have to worry that a new model will flop. There never need be a new model, per se, and if you do something to the software that users hate, you'll know right away. You have no trouble with uncollectible bills; if someone won't pay, you can just turn off the service. And there is no possibility of piracy.

That last "advantage" may turn out to be a problem. Some amount of piracy is to the advantage of software companies. If some user would never have bought your software at any price, you haven't lost anything if he uses a pirated copy. In fact you gain, because he is one more user helping to make your software the standard—or who might buy a copy later, when he graduates from high school.

When they can, companies like to do something called price discrimination, which means charging each customer as much as they can afford.9 Software is particularly suitable for price discrimination, because the marginal cost is close to zero. This is why some software costs more to run on Suns than on Intel boxes: a company that uses Suns is not interested in saving money and can safely be charged more. Piracy is effectively the lowest tier of price discrimination. I think software companies understand this and deliberately turn a blind eye to some kinds of piracy.10 With server-based software they will have to come up with some other solution.

Web-based software sells well, especially in comparison to desktop software, because it's easy to buy. You might think that people decide to buy something, and then buy it, as two separate steps. That's what I thought before Viaweb, to the extent I thought about the question at all. In fact the second step can propagate back into the first: if something is hard to buy, people will change their mind about whether they wanted it. And vice versa: you'll sell more of something when it's easy to buy. I buy more new books because Amazon exists. Web-based software is just about the easiest thing in the world to buy, especially if you have just done an online demo. Users should not have to do much more than enter a credit card number. (Make them do more at your peril.)

Sometimes web-based software is offered through ISPs acting as resellers. This is a bad idea. You have to be administering the servers, because you need to be constantly improving both hardware and software. If you give up direct control of the servers, you give up most of the advantages of developing web-based applications.

Several of our competitors shot themselves in the foot this way—usually, I think, because they were overrun by suits who were excited about this huge potential channel, and didn't realize that it would ruin the product they hoped to sell through it. Selling web based software through ISPs is like selling sushi through vending machines.

Who will the customers be? At Viaweb they were initially individuals and smaller companies, and I think this will be the rule with web-based applications. These are the users who are ready to try new things, partly because they're more flexible, and partly because they want the lower costs of new technology.

Web-based applications will often be the best thing for big companies too (though they'll be slow to realize it). The best intranet is the Internet. If a company uses true web-based applications, the software will work better, the servers will be better administered, and employees will have access to the system from anywhere.

The argument against this approach usually hinges on security: if access is easier for employees, it will be for bad guys too. Some larger merchants were reluctant to use Viaweb because they thought customers' credit card information would be safer on their own servers. It was not easy to make this point diplomatically, but in fact the data was almost certainly safer in our hands than theirs. Who can hire better people to manage security, a technology startup whose whole business is running servers, or a clothing retailer? Not only did we have better people worrying about security, we worried more about it. If someone broke into the clothing retailer's servers, it would affect at most one merchant, could probably be hushed up, and in the worst case might get one person fired. If someone broke into ours, it could affect thousands of merchants, would probably end up as news on CNet, and could put us out of business.

If you want to keep your money safe, do you keep it under your mattress at home, or put it in a bank? This argument applies to every aspect of server administration: not just security, but uptime, bandwidth, load management, backups, etc. Our existence depended on doing these things right. Server problems were the big no-no for us, like a dangerous toy would be for a toy maker, or a salmonella outbreak for a food processor.

A big company that uses web-based applications is to that extent outsourcing IT. Drastic as it sounds, I think this is generally a good idea. Companies are likely to get better service this way than they would from in-house system administrators. System administrators can become cranky and unresponsive because they're not directly exposed to competitive pressure. A salesman has to deal with customers, and a developer has to deal with competitors' software, but a system administrator, like an old bachelor, has few external forces to keep him in line.11 At Viaweb we had external forces in plenty to keep us in line. The people calling us were customers, not just co-workers. If a server got wedged, we jumped. Just thinking about it gives me a jolt of adrenaline, years later.

So web-based applications will ordinarily be the right answer for big companies too. They will be the last to realize it, however, just as they were with desktop computers. And partly for the same reason: it will be worth a lot of money to convince big companies that they need something more expensive.

There is always a tendency for rich customers to buy expensive solutions, even when cheap solutions are better, because the people offering expensive solutions can spend more to sell them. At Viaweb we were always up against this. We lost several high-end merchants to web consulting firms who convinced them they'd be better off if they paid half a million dollars for a custom-made online store on their own server. They were, as a rule, not better off, as more than one discovered when Christmas shopping season came around and loads rose on their server. Viaweb was a lot more sophisticated than what most of these merchants got, but we couldn't afford to tell them. At $300 a month, we couldn't afford to send a team of well-dressed and authoritative-sounding people to make presentations to customers.

At times we toyed with the idea of a new service called Viaweb Gold. It would have exactly the same features as our regular service, but would cost ten times as much would be sold in person by a man in a suit. We never got around to offering this variant, but I'm sure we could have signed up a few merchants for it.

A large part of what big companies pay extra for is the cost of selling expensive things to them. (If the Defense Department pays a thousand dollars for toilet seats, it's partly because it costs a lot to sell toilet seats for a thousand dollars.) And this is one reason intranet software will continue to thrive, even though it is probably a bad idea. It's simply more expensive. There is nothing you can do about this conundrum, so the best plan is to go for the smaller customers first. The rest will come in time.

Running software on the server is nothing new. In fact it's the old model: mainframe applications are all server-based. If server based software is such a good idea, why did it lose last time? Why did desktop computers eclipse mainframes?

At first desktop computers didn't look like much of a threat. The first users were all hackers—or hobbyists, as they were called then. They liked microcomputers because they were cheap. For the first time, you could have your own computer. The phrase "personal computer" is part of the language now, but when it was first used it had a deliberately audacious sound, like the phrase "personal satellite" would today.

Why did desktop computers take over? Mainly because they had better software. And the reason microcomputer software was better was that it could be written by small companies.

I don't think many people realize how fragile and tentative startups are in the earliest stage. Many startups begin almost by accident—as a couple guys, either with day jobs or in school, writing a prototype of something that might, if it looks promising, turn into a company. At this larval stage, any significant obstacle will stop the startup dead in its tracks. Writing mainframe software required too much commitment up front. Development machines were expensive, and because the customers would be big companies, you'd need an impressive-looking sales force to sell it to them. Starting a startup to write mainframe software would be a much more serious undertaking than just hacking something together on your Apple II in the evenings. And so you didn't get a lot of startups writing mainframe applications.

The arrival of desktop computers inspired a lot of new software, because writing applications for them seemed an attainable goal to larval startups. Development was cheap, and the customers would be individual people that you could reach through computer stores or even by mail-order.

The application that pushed desktop computers out into the mainstream was VisiCalc, the first spreadsheet. It was written by two guys working in an attic, and yet did things no mainframe software could do.12 VisiCalc was such an advance, in its time, that people bought Apple IIs just to run it. And this was the beginning of a trend: desktop computers won because startups wrote software for them.

It looks as if server-based software will be good this time around, because startups will write it. Computers are so cheap now that you can get started, as we did, using a desktop computer as a server. Inexpensive processors have eaten the workstation market (you rarely even hear the word now) and are most of the way through the server market; Yahoo's servers, which deal with loads as high as any on the Internet, all have the same inexpensive Intel processors that you have in your desktop machine. And once you've written the software, all you need to sell it is a web site. Nearly all our users came direct to our site through word of mouth and references in the press.13

Viaweb was a typical larval startup. We were terrified of starting a company, and for the first few months comforted ourselves by treating the whole thing as an experiment that we might call off at any moment. Fortunately, there were few obstacles except technical ones. While we were writing the software, our web server was the same desktop machine we used for development, connected to the outside world by a dialup line. Our only expenses in that phase were food and rent.

There is all the more reason for startups to write web-based software now, because writing desktop software has become a lot less fun. If you want to write desktop software now, you do it on Microsoft's terms, calling their APIs and working around their buggy OS. And if you manage to write something that takes off, you may find that you were merely doing market research for Microsoft.

If a company wants to make a platform that startups will build on, they have to make it something that hackers themselves will want to use. That means it has to be inexpensive and well-designed. The Mac was popular with hackers when it first came out, and a lot of them wrote software for it.14 You see this less with Windows, because hackers don't use it. The kind of people who are good at writing software tend to be running Linux or FreeBSD now.

I don't think we would have started a startup to write desktop software, because desktop software has to run on Windows, and before we could write software for Windows we'd have to use it. The Web let us do an end-run around Windows, and deliver software running on Unix direct to users through the browser. That is a liberating prospect, a lot like the arrival of PCs twenty-five years ago.

Back when desktop computers arrived, IBM was the giant that everyone feared. It's hard to imagine now, but I remember the feeling well. Now the frightening giant is Microsoft, and I don't think they are as blind to the threat facing them as IBM was. After all, Microsoft deliberately built their business in IBM's blind spot.

I mentioned earlier that my mother doesn't really need a desktop computer. Most users probably don't. That's a problem for Microsoft, and they know it. If applications run on remote servers, no one needs Windows. What will Microsoft do? Will they be able to use their control of the desktop to prevent, or constrain, this new generation of software?

I expect Microsoft will develop some kind of server/desktop hybrid, where the operating system works together with servers they control. At a minimum, files will be centrally available for users who want that. I don't expect Microsoft to go all the way to the extreme of doing the computations on the server, with only a browser for a client, if they can avoid it. If you only need a browser for a client, you don't need Microsoft on the client, and if Microsoft doesn't control the client, they can't push users towards their server-based applications.

I think Microsoft will have a hard time keeping the genie in the bottle. There will be too many different types of clients for them to control the mall. And if Microsoft's applications only work with some clients, competitors will be able to trump them by offering applications that work from any client.15

In a world of web-based applications, there is no automatic place for Microsoft. They may succeed in making themselves a place, but I don't think they'll dominate this new world as they did the world of desktop applications.

It's not so much that a competitor will trip them up as that they will trip over themselves. With the rise of web-based software, they will be facing not just technical problems but their own wishful thinking. What they need to do is cannibalize their existing business, and I can't see them facing that. The same single-mindedness that has brought them this far will now be working against them. IBM was in exactly the same situation, and they couldn't master it. IBM made a late and half-hearted entry into the microcomputer business because they were ambivalent about threatening their cash cow, mainframe computing. Microsoft will likewise be hampered by wanting to save the desktop. A cash cow can be a heavy monkey on your back.

I'm not saying that no one will dominate server-based applications. Someone probably will eventually. But I think there will be a good long period of cheerful chaos, just as there was in the early days of microcomputers. That was a good time for startups. Lots of small companies flourished, and did it by making cool things.

The classic startup is fast and informal, with few people and little money. Those few people work very hard, and technology magnifies the effect of the decisions they make. If they win, they win big.

In a startup writing web-based applications, everything you associate with startups is taken to an extreme. You can write and launch a product with even fewer people and even less money. You have to be even faster, and you can get away with being more informal. You can literally launch your product as three guys operating out of an apartment, with a server collocated at an ISP. We did.

Over time the teams have gotten smaller, faster, and more informal. In 1960, software development meant a roomful of men with horn-rimmed glasses and narrow black neckties, industriously writing ten lines of code a day on IBM coding forms. In 1980, it was a team of eight to ten people wearing jeans to the office and typing into VT100s. Now it's a couple of guys sitting in a living room with laptops. (And jeans turn out not to be the last word in informality.)

Startups are stressful, and this, unfortunately, is also taken to an extreme with web-based applications. Many software companies, especially at the beginning, have periods where the developers slept under their desks and so on. The alarming thing about web based software is that there is nothing to prevent this becoming the default. The stories about sleeping under desks usually end: then at last we shipped it, and we all went home and slept for a week. Web-based software never ships. You can work 16-hour days for as long as you want to. And because you can, and your competitors can, you tend to be forced to. You can, so you must. It's Parkinson's Law running in reverse.

The worst thing is not the hours but the responsibility. Programmers and system administrators traditionally each have their own separate worries. Programmers worry about bugs, and system administrators worry about infrastructure. Programmers may spend a long day up to their elbows in source code, but at some point they get to go home and forget about it. System administrators never quite leave the job behind, but when they do get paged at 4:00 AM, they don't usually have to do anything very complicated. With web-based applications, these two kinds of stress get combined. The programmers become system administrators, but without the sharply defined limits that ordinarily make the job bearable.

At Viaweb we spent the first six months just writing software. We worked the usual long hours of an early startup. In a desktop software company, this would have been the hard part, but it felt like a vacation compared to the next phase, when we took users onto our server. The second biggest benefit of selling Viaweb to Yahoo (after the money) was to be able to dump ultimate responsibility for the whole thing onto the shoulders of a big company.

Desktop software forces users to become system administrators. Web-based software forces programmers to. There is less stress in total, but more for the programmers. That's not necessarily bad news. If you're a startup competing with a big company, it's good news.16 Web-based applications offer a straightforward way to outwork your competitors. No startup asks for more.

One thing that might deter you from writing web-based applications is the lameness of web pages as a UI. That is a problem, I admit. There were a few things we would have really liked to add to HTML and HTTP. What matters, though, is that web pages are just good enough.

There is a parallel here with the first microcomputers. The processors in those machines weren't intended to be the CPUs of computers. They were designed to be used in things like traffic lights. But guys like Ed Roberts, who designed the Altair, realized that they were just good enough. You could combine one of these chips with some memory (256 bytes in the first Altair), and front panel switches, and you'd have a working computer. Being able to have your own computer was so exciting that there were plenty of people who wanted to buy them, however limited.

Web pages weren't designed to be a UI for applications, but they're just good enough. And for a significant number of users, software you can use from any browser will be enough of a win in itself to outweigh any awkwardness in the UI. Maybe you can't write the best-looking spreadsheet using HTML, but you can write a spreadsheet that several people can use simultaneously from different locations without special client software, or that can incorporate live data feeds, or that can page you when certain conditions are triggered. More importantly, you can write new kinds of applications that don't even have names yet. VisiCalc was not merely a microcomputer version of a mainframe application, after all—it was a new type of application.

Figure 5-1. Popular Electronics, January 1975 (detail).

Of course, server-based applications don't have to be web based. You could have some other kind of client. But I'm pretty sure that's a bad idea. It would be very convenient if you could assume that everyone would install your client—so convenient that you could easily convince yourself that they all would. But if they don't, you're hosed.

Because web-based software assumes nothing about the client, it will work anywhere the Web works. That's a big advantage already, and the advantage will grow as new web devices proliferate. Users will like you because your software just works, and your life will be easier because you won't have to tweak it for every new client.17

I feel like I've watched the evolution of the Web as closely as anyone, and I can't predict what's going to happen with clients. Convergence is probably coming, but where?

How will it all play out? I don't know. And you don't have to know if you bet on web-based applications. No one can break that without breaking browsing. The Web may not be the only way to deliver software, but it's one that works now and will continue to work for a long time. Web-based applications are cheap to develop, and easy for even the smallest startup to deliver. They're a lot of work, and of a particularly stressful kind, but that only makes the odds better for startups.

E. B. White was amused to learn from a farmer friend that many electrified fences don't have any current running through them. The cows apparently learn to stay away from them, and after that you don't need the current. "Rise up, cows!" he wrote. "Take your liberty while despots snore!"

If you're a hacker who has thought of one day starting a startup, there are probably two things keeping you from doing it. One is that you don't know anything about business. The other is that you're afraid of competition. Neither of these fences have any current in them.

There are only two things you have to know about business: build something users love, and make more than you spend. If you get these two right, you'll be ahead of most startups. You can figure out the rest as you go.

You may not at first make more than you spend, but as long as the gap is closing fast enough you'll be ok. If you start out under funded, it will at least encourage a habit of frugality. The less you spend, the easier it is to make more than you spend. Fortunately, it can be very cheap to launch a web-based application. We launched on under $10,000, and it would be even cheaper today. We had to spend thousands on a server, and thousands more to get SSL. (The only company selling SSL software at the time was Netscape.) Now you can rent a much more powerful server, with SSL included, for less than we paid for bandwidth alone. You could launch a web-based application now for less than the cost of a fancy office chair.

As for building something users love, here are some general tips. Start by making something clean and simple that you would want to use yourself. Get a version 1.0 out fast, then continue to improve the software, listening closely to users as you do. The customer is always right, but different customers are right about different things; the least sophisticated users show you what you need to simplify and clarify, and the most sophisticated tell you what features you need to add. The best thing software can be is easy, but the way to do this is to get the defaults right, not to limit users' choices. Don't get complacent if your competitors' software is lame; the standard to compare your software to is what it could be, not what your current competitors happen to have. Use your software yourself, all the time. Viaweb was supposed to be an online store builder, but we used it to make our own site too. Don't listen to marketing people or designers or product managers just because of their job titles. If they have good ideas, use them, but it's up to you to decide; software has to be designed by hackers who understand design, not designers who know a little about software. If you can't design software as well as implement it, don't start a startup.

Now let's talk about competition. What you're afraid of is not presumably groups of hackers like you, but actual companies, with offices and business plans and salesmen and so on, right? Well, they are more afraid of you than you are of them, and they're right. It's a lot easier for a couple of hackers to figure out how to rent office space or hire sales people than it is for a company of any size to get software written. I've been on both sides, and I know. When Viaweb was bought by Yahoo, I suddenly found myself working for a big company, and it was like trying to run through waist-deep water.

I don't mean to disparage Yahoo. They had some good hackers, and the top management were real butt-kickers. For a big company, they were exceptional. But they were still only about a tenth as productive as a small startup. No big company can do much better than that. What's scary about Microsoft is that a company so big can develop software at all. They're like a mountain that can walk.

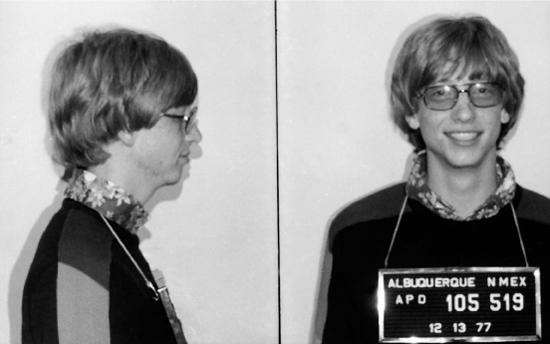

Figure 5-2. Bill Gates, 1977.

Don't be intimidated. You can do as much that Microsoft can't as they can do that you can't. And no one can stop you. You don't have to ask anyone's permission to develop web-based applications. You don't have to do licensing deals, or get shelf space in retail stores, or grovel to have your application bundled with the OS. You can deliver software right to the browser, and no one can get between you and potential users without preventing them from browsing the Web.

You may not believe it, but I promise you, Microsoft is scared of you. The complacent middle managers may not be, but Bill is, because he was you once, back in 1975, the last time a new way of delivering software appeared.

Copyright ©2010-2022 比特日记 All Rights Reserved.